Superintendents, unions, and the Kansas Association of School Boards hounded the Legislature for more special education funding last year, saying general education services were curtailed because they had to transfer so much money to special education. Their own budgets refuted their claims then, and new cash reserve data proves it again.

The total special education cash reserve balance was $273.6 million at the end of the 2024 school year, which is an increase of $18.6 million over the prior year, leading to two vital takeaways:

- School administrators transferred $18.6 million more than needed to maintain special education cash reserves and,

- School administrators are holding too much money in special education cash reserves. Many districts maintain very low balances (seven have a zero balance).

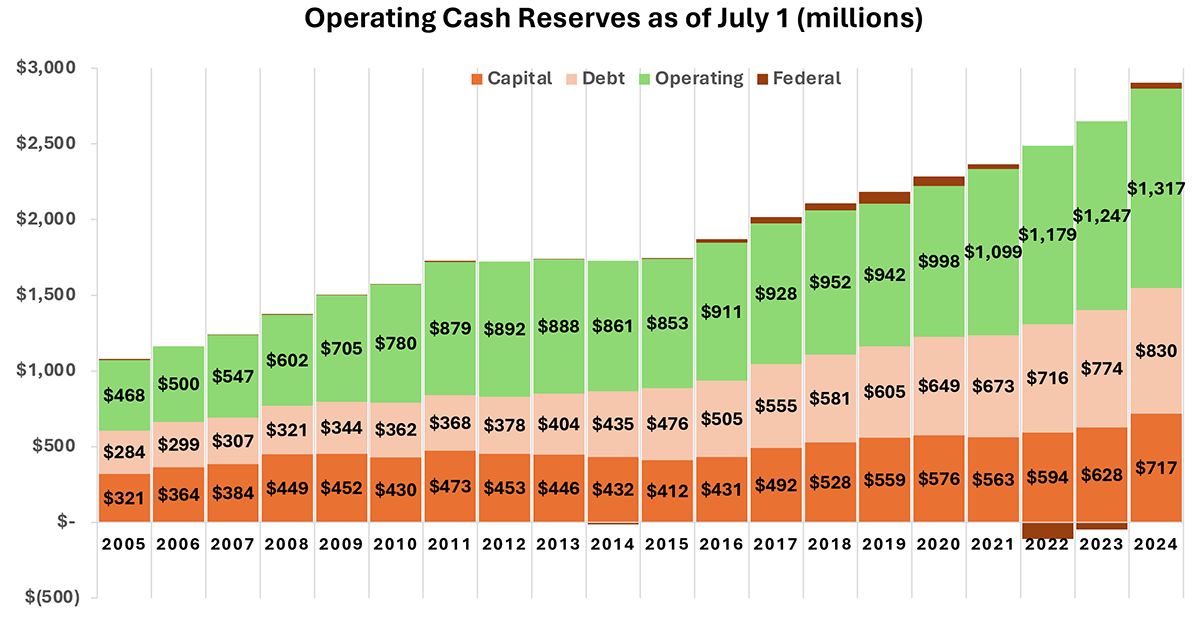

Total operating cash reserves, including special education, are $1.317 billion. The increase of more than $60 million from the previous year means administrators didn’t spend all the money they collected to educate students in the last school year.

Since 2005, school districts have increased operating cash reserves by nearly $850 million. Balances for each school district are available at KansasOpenGov.org.

Cash reserve growth is similar to personal checkbooks

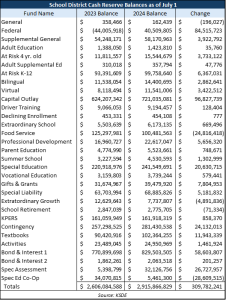

The adjacent table shows that school districts can have more than 30 fund balances, which operate similarly to checkbooks.

Imagine having multiple personal checkbooks to track your spending habits. There might be checkbooks for home maintenance, food, education expenses, auto expenses, etc. Your paycheck is deposited into a general fund checking account (maybe for non-specified costs), and then you transfer money to the other accounts.

Some fund balances can only be spent for specified purposes, like special education. Other funds are unrestricted, meaning the money in them can be spent for anything allowed by law, and balances in those funds can be transferred to other funds.

The Kansas Department of Education says a fund balance is unnecessary when spending money for a particular purpose, but the money must exist somewhere. Let’s say a district keeps a zero balance in a restricted fund (like Special Education) and has $10 million in other operating funds at the beginning of the year. The district spends $1 million during the year in that restricted fund and transfers $1 million from another fund, finishing the year with a zero balance in the restricted fund.

Smart cash management prevents money from becoming trapped in restricted funds and allows districts to have less money in reserve.

Administrators want more money, but they don’t need it

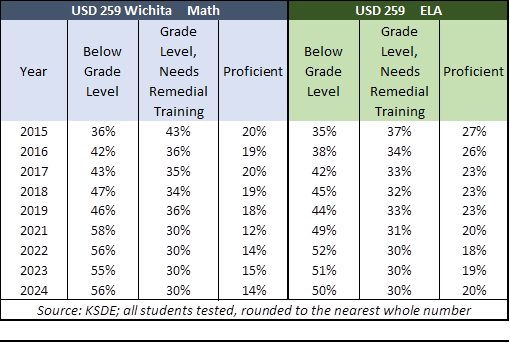

School administrators continually demonstrate that they have plenty of money to educate students; they may not be spending it effectively, but the money is there.

They also know that the Kansas Supreme Court approved the Legislature’s plan to fund schools, including specific increases in special education that have been provided each year. Unfortunately, the Legislature didn’t remove a statutory reference to special education funding that conflicts with the school funding settlement, and education administrators are using that to demand even more money from taxpayers.

Taxpayers already provide more than $18,000 per student, which is more than adequate.