Thirty-four percent of fourth-grade students in the United States cannot read at the basic level, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

It may not be unreasonable, then, to conclude that a third of fourth graders are, therefore, functionally illiterate.

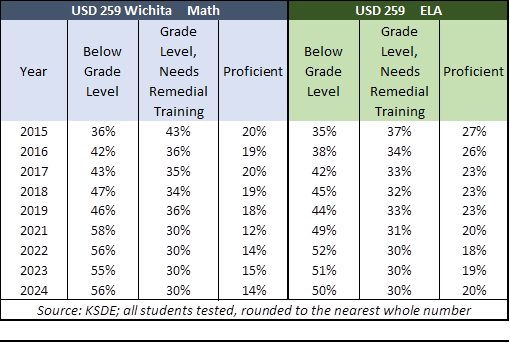

In Kansas, the numbers are falling and even worse than the national average, with 40% of fourth graders below the basic level and only 30% proficient.

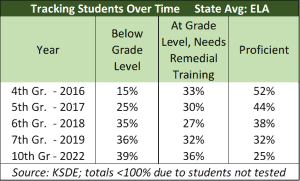

On the state assessment, which has different standards, a decline in proficiency over time was stark: 39% of 10th-graders were below grade level in 2022 and only 25% were proficient. When that class was in the 4th grade in 2016, just 15% were below grade level, and 52% were proficient. The impact of not having strong reading skills when students transition from learning how to read to reading in order to learn is seen in proficiency declines over their school career.

According to Dr. David Hurford, director of the Center for Research, Evaluation and Awareness of Dyslexia — or READing — at Pittsburg State University in Pittsburg, Kansas, runs a nationally-recognized program that teaches dyslexic children and adults to read, it is a situation which should not only be unacceptable but doesn’t have to happen.

“Thirty-four percent of our nation’s children are not reading at the basic level,” Hurford said. “The National Center for Education Statistics defines reading at the basic level as ‘partial mastery of fundamental skills.’ Not reading at the basic level then indicates that the student does not have a ‘partial mastery of fundamental skills,’ which is sad.”

It is not just students who are struggling, Hurford said.

“There are approximately 93 million adults who cannot read well enough to take their prescription medication,” he said. “The illiteracy rate of adults is simply an outgrowth of poor reading instruction while in school.”

But, Hurford said, the very same techniques his department uses to teach dyslexic children and adults to read should be used to teach every child to read.

It’s called “the Science of Reading,” and other states with historically high illiteracy rates are using it to make historic gains.

According to the Associated Press, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama have turned to the science of reading to fix a long-standing problem.

“Mississippi went from being ranked the second-worst state in 2013 for fourth-grade reading to 21st in 2022,” the AP report reads. “Louisiana and Alabama, meanwhile, were among only three states to see modest gains in fourth-grade reading during the pandemic, which saw massive learning setbacks in most other states.”

Hurford said the issue is that most people don’t think about reading in terms of a “science.”

“Everyone has their opinion on how reading should be taught,” he said. “Although there is a science of reading, and of course, it seems strange to say ‘the science of reading’ because you don’t say ‘the science of biology’ because we know biology is a science. We don’t say ‘the science of physics’ because we know physics is a science.

“But for 120 years, we’ve been using methods to teach reading that are not science-based. And so we need to really hammer that science of reading because there are thousands of studies that have been published at this point in time that really do indicate how we should be teaching reading.”

It’s something even the New York Times is stressing as well, reporting recently, “Research shows that most children need systematic, sound-it-out instruction — known as phonics — as well as other direct support, like building vocabulary and expanding students’ knowledge of the world.”

Over the last two years, almost 20 states have started the same push that Mississippi made in 2019 — with the same “startling” results, which probably should not have been a surprise.

“A popular method of teaching, known as ‘balanced literacy,’ has focused less on phonics and more on developing a love of books and ensuring students understand the meaning of stories,” theTimes reports. “At times, it has included dubious strategies, like guiding children to guess words from pictures.”

Hurford said the issue is the notion there are “many ways” to teach reading.

“In reality, there isn’t,” he said. “We need to teach the mechanics of reading; that notion that this letter represents this sound. And then you can decode that letter into the sound, synthesize and blend it together, and then have some recognition that what you’re reading is a word you already know.”

The Sentinel reached out to Kansas Commissioner of Education Dr. Randy Watson, to ask if the Kansas State Department of Education — which has a requirement for “structured literacy and/or dyslexia training” — if the science of reading being used by the Center for READing and other states is recommended by KSDE.

Two emails returned received and read receipts, but as of publication, Watson had not responded.

According to the KSDE website, “The Legislative Task Force on Dyslexia and the Kansas State Board of Education have required that schools conduct annual professional development on structured literacy and/or dyslexia. Professional learning is required annually but each school system is allowed to determine the time and duration of the training. The training should be hands-on, with evidence-based practices, on the nature of dyslexia, procedures to identify students who are struggling in reading, intervention strategies and procedures, tiered intervention practices, or progress monitoring.”

But what “evidence-based” practices are required appears to be left to the districts.

For Hurford, the bottom line is simple — reading is a science, and anyone can learn — if they’re taught properly.

“If students do not learn to read while in school, they will not magically become competent readers once they leave,” he said. “That is beginning to change, though, which is wonderful. That change occurs because parents require that their children learn to read. Legislators, families, teachers, and reporters are helping to make people aware of the issue.

“We are finally getting there.”