Leaders of the Kansas House Committee on Higher Education Budget are declining to answer questions about stripping $8 million in funding from the Kansas Blueprint for Literacy.

Passed in the 2024 state legislative session, the Blueprint — which had overwhelming bipartisan support — not only enshrined the evidence-based method of teaching literacy called the “Science of Reading” in state law but set aggressive targets for student achievement improvement and created a new 15-member Literacy Advisory Committee along with a “Director of Literacy Education.”

The law also required the establishment of regional Centers of Excellence in Reading and provided for funding to train teachers and student teachers in the Science of Reading.

House Bill 2007 originally appropriated $10 million to fund Blueprint implementation, but the House passed an amended bill Wednesday changing that to “not less than $2 million.”

The Sentinel contacted state reps. Steven Howe and Clarke Sanders — the chair and vice chair of the Higher Ed Budget Committee respectively — asking why the funding was cut, but received no answer.

Dr. Blake Flanders, president of the Kansas Board of Regents, said the funding cuts are going to make it difficult to implement what the law requires.

“That’s a concern, certainly for me, and should be a concern for Kansans because we aren’t getting to the level I think that we want each child to get to in terms of reading ability,” Flanders said.

Flanders said he had heard some concern from legislators that the centers were perhaps not the right approach, but said that the plan for the centers was developed because it was a requirement of the legislation.

Flanders agreed that centers like the Phillips Fundamental Learning Center in Wichita or the Center for Research, Evaluation, and Awareness of Dyslexia at Pittsburg State University would not be the solution for every student but said that they needed to be looked at as a nexus or “network” for bringing the Blueprint “to scale.”

“This is an issue, though, of really trying to get to scale on the training and the retraining of individual teachers to give them the tools they need to be successful,” Flanders said. “We need a broad understanding of just how many individuals that means. I mean, if, if you just really look at the number of elementary educators, it’s over 18,000.”

Flanders said a little over 3,700 have completed “letters training” — the theoretical base for individuals in structured literacy.

“That’s a really good start,” Flanders said. “But if we’re going to move these numbers, we have to get to scale quickly, and we probably need some hands-on training.

“It’s one thing to know the theoretical, which is important, but … for a comprehensive solution, people are going to have to have guided practice and be drilled in how to teach the science of reading,” Flanders said. “What we’ve seen nationally is that the investment in literacy coaches has seemed to be something that’s moving the needle.

“We have to get solutions that are ‘both and’ those kinds of deep dive solutions that our partners are very good at. Pittsburg State, the Fundamental Learning Center in Wichita, the (other) service centers do some of that work. I see that as critical as well. But then we have to have a way to deploy coaches, particularly in our some of our rural counties that have higher numbers of students that can’t read.”

Flanders said he sees the literacy centers — if properly funded — as being able to train those literacy coaches and other educators, who then go out to the other districts to train educators there.

It really is about the resources,” Flanders said. “So if you think about a third of the kids not reading well, you probably are going to have difficulty bussing a third of the students to a different building, perhaps a center, and get to scale.

“That’s a solution that you cannot likely scale across the numbers that we need, and so we’re going to have to help parents and families within those schools and actually empower existing teachers and education leaders to do that, and that means getting them the resources they need. You know, guiding that teacher to analyze the data, to plan instruction, helping them to develop plans, showing them models for small group instruction.”

NEAP scores show literacy rates remain low

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), acknowledged as the “gold standard” of assessments by the Kansas Department of Education, shows Kansas students once again are performing below the national average in reading and math.

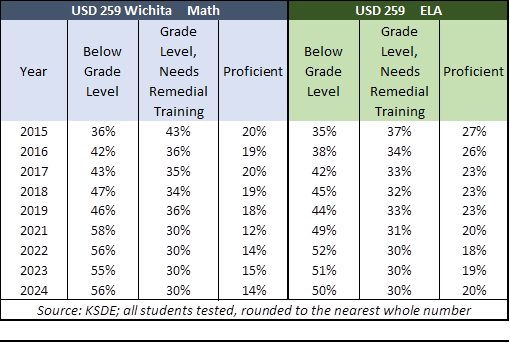

The 2024 results show the state’s precipitous decline in literacy continues, with more students Below Basic (at least some of whom are functionally illiterate) than are proficient. Results were never what many people might call ‘good,’ but a serious decline began around 2015, which is when the Kansas State Board of Education began de-emphasizing academic preparation with its “Kansans Can” program. For example, the portion of Kansas 8th-graders Below Basic went from 21% in 2015 to 34% now, while proficiency dropped from 35% to 25%.

Results in 4th-grade reading show similar trends.

Students reading Below Basic jumped from 32% to 40%, while the proficiency level plummeted from 35% to 25%.